Abstract

The purpose of this research is to identify a connection between Problem-Focused Coping and Openness to Experience. Problem-Focused Coping is a coping style formulated from a cluster of responses on the Brief COPE that is characterized by actively working to confront negative thoughts and experiences. Openness to Experiences is the dimension of the Big Five Index that is closely related to intelligence and creativity. The research will involve the administration of Brief COPE and Big Five Index measures to voluntary participants gathered from TUJ’s First-Year Writing Program. The responses related to Problem-Focused Coping and Openness to Experience will be used to create a composite score that will compare responses. The goal of this research is to be the first step toward determining which characteristics found in people lead to positive adaptation to negative life experiences.

Keywords: Problem-Focused Coping, Openness to Experience

The Connection Between Problem-Focused Coping and Openness to Experience

While it may seem automatic to focus on negative responses to stress, there are many examples of coping styles that are very positive in nature. Thankfully, in the modern world, some measures have changed such intangible concepts into ones that can be measured. Two of these measures are the Brief COPE and the Big Five Index. What could be the potential relationship between positive coping strategies as measured by the Brief COPE and high Openness to Experience scores on the Big Five Index?

Definitions

Problem-Focused Coping has been defined as strategies aimed at solving and actively responding to stressful situations. (Baumstarck et al)

Openness to experience is one of the domains which are used to describe human personality in the Five-Factor Model. Openness involves six facets, or dimensions, including active imagination (fantasy), aesthetic sensitivity, attentiveness to inner feelings, preference for variety, and intellectual curiosity. (Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R., 1992)

Historical Examples of Positive Coping Strategies to Traumatic Experiences

Positive adaptations to negative experiences have been a topic of interest for centuries, which continues to this day and is a common theme in the realm of literature. According to Stroe:

“Deep pain and exuberant joy are the two facets of Mary Shelley’s biography and literary output. In order to better understand the connections between trauma (physical or psychological) and forms of (literary) creativity, and in order to better answer questions related to the genesis of the still enigmatic Frankenstein and its remarkable creator, we need to focus on the intricate network of events in this author’s life and on the complexities of her literary works and thought.” (Stroe, M. A., 2013)

In addition to this, it was posited that: “Positive adaptation to psychological trauma and wisdom both have a rich history in European literature and philosophy. Although the literature on posttraumatic growth has recognized the possibility of wisdom as an outcome of adaptation, its role in the process of adaptation has been neglected.” (Linley, P. A., 2003)

While this data is not empirical in nature, it leads to the concepts of both Openness to Experience and Problem-Focused Coping and informs of the importance of this type of research. To be defined in an operational sense, this type of positive adaptation could potentially be understood as Openness to Experience scores on the Big Five Index, while the facilitating factor for this trait could be understood as Problem-Focused Coping as per the Brief COPE.

Empirical Studies

There have already been studies that have attempted to link adverse life experiences to personality traits. In 2016, the results of a study were published which was conducted comparing The Junior Eysenck Personality Inventory (JEPI) scores of traumatized youth with or without PTSD to the scores of a non-traumatized control group. It was observed that the PTSD group had significantly higher JEPI Neuroticism scores relative to the comparison groups. (Saigh et al, 2016)

In addition to studies linking adverse life experiences to personality traits, there have also been studies that have attempted to categorize response factors that people have developed in response to trauma. An example of this type of study is the one that was published in 2012 that utilized a dataset of veterans with a high prevalence of PTSD. It evaluated whether a two (Internalizing, Externalizing) or three (Distress, Fear, Externalizing) factor model was better for locating the area for comorbidity between PTSD and Borderline Personality Disorder (Miller et al, 2012)

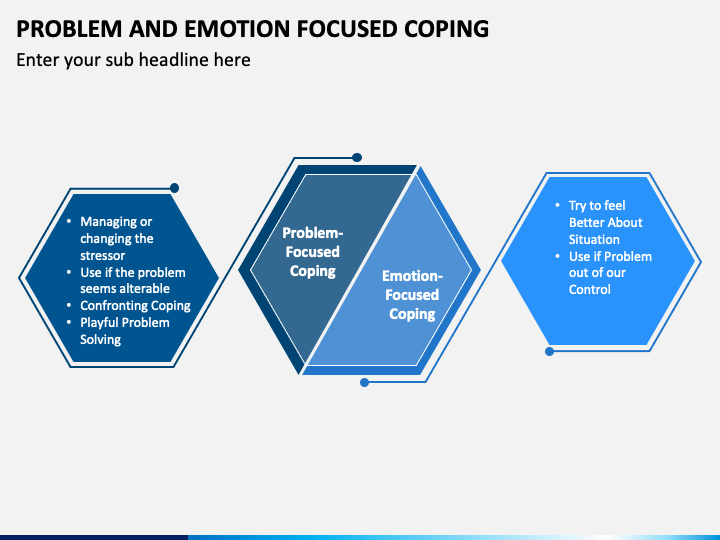

As a means of categorizing different clusters of coping strategies, Folkman and Lazarus (1980) distinguished between problem-focused coping, which is focused on strategies aimed at solving and actively responding to stressful situations, and emotion-focused coping, which focuses on strategies to manage or reduce emotions and feelings that are embedded within stressful situations. Expounding upon this, Carver, Scheier, and Weintraub (1989) distinguished between approach coping, which focuses on strategies aimed at dealing actively confronting the stressor or related emotions, and avoidance coping which focuses on strategies aimed at avoiding stressful situations.

While Problem-Focused Coping is merely a concept contrived from a derivative grouping of responses in accordance with the Brief COPE, the grouping is still based upon the same standardized index, and could easily be compared to responses on the Big Five Index, through which Openness to Experience is derived in the same fashion.

As a means of expanding this research, the presented research has led to the hypothesis that there is a significant relationship between Problem-Focused Coping as per Brief COPE scores and Openness to Experience as per the Big Five Index.

Methods

Participants

During the Fall 2016 and Spring 2017 students in TUJ’s First-Year Writing Program were surveyed. Courses included sections of Introduction to Academic Discourse for native speakers of English and sections of the same course for students whose second language is English In addition to these classes, students from sections of Analytical Reading and Writing for native speakers and those whose second language is English were included. Of these participants, 107 provided the necessary responses to both the Brief COPE and Big Five Index sections The majority of the participants were Male (49%).

Measures

The course instructor read instructions and students were given time in class to complete five measures throughout the term. Surveys 1 and 2 were developed by Ada Angel for the First-Year Writing Program. Survey 1 included demographic, achievement goals, and attitude toward writing measures Survey 2, included self-efficacy measures. The last three measures included (a) a personality measure, the Big Five (John, Naumann; Soto, 2008) (b) the Coping Orientation to Problem Experienced (COPE, Carver, Scheier; Weintraub, 1989), and (c) Grit xxx Additional measures included the student’s final course grade. For my study, I utilized the Brief COPE and the Big Five Index.

The Brief COPE. An index measures 14 theoretically identified coping responses: Self-distraction, Active coping, Denial, Substance use, Use of emotional support, Use of instrumental support, Behavioral disengagement, Venting, Positive reframing, Planning, Humor, Acceptance, Religion, and Self-blame. It represents a way to rapidly measure coping responses because it is a short 28-item self-report questionnaire with two items for each of the measured coping strategies. (Monzani et al, 2015)

Big Five Index. An index that utilizes five factors that have been defined as openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism, often represented by the acronyms OCEAN or CANOE. Beneath each proposed global factor, there are several correlated and more specific primary factors. For example, extraversion is said to include such related qualities as gregariousness, assertiveness, excitement seeking, warmth, activity, and positive emotions. (Rothmann S, Coetzer EP, 2003)

Procedure

The purpose of the data collection, for the First-Year Writing Program evaluation and Psychological Studies course research, was explained to students at the start of the academic term. As each of the questionnaires was administered, students were reminded that their choice to respond was voluntary and that we would guarantee their anonymity and guarantee confidentiality of their

responses. During the first two weeks of class meetings, students completed Surveys 1 and 2. At the end of the academic term, during the last week of class meetings, students completed the Big Five, the COPE measures, Grit, and a consent form that permitted the researchers to use their responses program evaluation and research purposes.

Design

This study used a simple experiment with an independent samples t-test. The independent variable was Problem-Focused Coping as per the Brief COPE, and the dependent variable was Openness to Experience as per the Big Five Index. We randomly assigned participants to conditions.

Results

Means and standard deviations for the two experimental conditions were: Problem-Focused Coping (High) (M = 2.79, SD = .46), Problem-Focused Coping (High) (M = 3.06, SD = .53), Openness to Experience (Low) (M = 2.87, SD = .52), Openness to Experience (High) (M = 3.71, SD = .40). An independent samples t-test compared the Problem-Focused Coping to two levels of Openness to Experience. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for Problem-Focused Coping and Openness to Experience, and Table 2 shows the results of that analysis. As can be seen from the table, the analysis was significant and had a small effect size; t (104) = -2.27, p = .000 (two-tailed), effect size d = .22. This indicates that there was a significant difference between anchors such that lower anchors produced lower estimations and high anchors produced higher estimations.

Need Help With Editing? Click Here

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Problem-Focused Coping and Openness to Experience

| M | SD | 95% CI | Range | Skewness | SESkew | Kurtosis | SEKur | |||

| Lower | Upper | Minimum | Maximum | |||||||

| Openness to Experience (Low) | 2.79 | 0.46 | 2.75 | 3.01 | 1.70 | 3.40 | .-1.161 | .327 | 0.526 | .644 |

| Openness to Experience (High) | 3.06 | 0.53 | 3.73 | 3.90 | 3.40 | 4.80 | 1.056 | .327 | 1.154 | .644 |

| Problem-Focused Coping (Low) | 2.87 | 0.52 | 2.65 | 2.90 | 3.00 | 1.81 | -2.12 | .327 | -0.608 | .644 |

| Problem-Focused Coping (High) | 3.71 | 0.40 | 2.97 | 3.27 | 5.00 | 3.74 | -.474 | .327 | 0.001 | .644 |

Table 2. Independent Samples t test for Problem-Focused Coping and Openness to Experience

| N | t-crit | t-obs | df | p | 95% CI | d | Decision | ||

| Upper | Lower | ||||||||

| Openness to Experience | 107 | 1.66 | -12.363 | 104 | .001 | -.78416 | -1.08377 | 0.22 | Reject |

| Problem-Focused Coping | 107 | 1.66 | -12.363 | 104 | .001 | -0.15396 | -0.53337 |

Discussion

The goal of this particular study was to determine if there was a relationship between Problem-Focused Coping and Openness to Experience that could be considered significant. It was predicated that higher levels of Problem-Focused Coping would correspond to higher levels of Openness to Experience. As predicted, higher levels of both index scores did in fact correspond with each other. However, the strength of the effect was small.

Strengths & Limitations

The obvious first limitation of this study is the fact that all participants came from that same subject pool of participants, which naturally leads to bias in results and opens the door for the possibility of confounding factors. This makes it hard for these type of results to be generalizable to a greater population. The second issue is the fact that the study only focused on one type of coping method compared to one dimension of the Big Five Index. It would have been better to compare all of the dimensions at once to determine if there was a greater interaction.

Future Directions

The best direction to be taken with future research in this area would be to do a study that draws from a more diverse population in order to reduce potential bias in results and improve the quality of random sampling. In addition to this, it would be good to compare all four coping styles against all five dimensions of personality. It would also be good to look for relationship between coping styles trauma, as well as personality types and trauma.

Conclusion

This study wasn’t intended to be a stand-alone study, but to instead act as the starting point for the research into positive adaptations to trauma. It seemed like an obvious starting point to look at a single point of connection between one coping style and personality dimension to determine if this research direction has any merit. Thankfully, a significant relationship was found, therefore this could potentially be the beginning of a very fruitful line of research. By finding how positive adaptions to such negative life experiences to trauma, maybe the effects of trauma can be mitigated.

References

Baumstarck, K., Alessandrini, M., Hamidou, Z., Auquier, P., Leroy, T., & Boyer, L. (2017). Assessment of coping: A new french four-factor structure of the brief COPE inventory. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0581-9

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, K. J. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 2267-283. https://doi.org/ 10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267

Contractor, A. A., Armour, C., Shea, M. T., Mota, N., ; Pietrzak, R. H. (2016). Latent profiles of DSM-5 PTSD symptoms and the “Big Five” personality traits. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 37, 10-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.10.005

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. (1992). NEO personality Inventory professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 3219-239. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136617

Linley, P. A. (2003). Positive adaptation to trauma: Wisdom as both process and outcome. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16(6), 601-610. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:jots.0000004086.64509.09

Miller, M. W., Wolf, E. J., Reardon, A., Greene, A., Ofrat, S., & McInerney, S. (2012). Personality and the latent structure of PTSD comorbidity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 1-9. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

Monzani, D., Steca, P., Greco, A., D’Addario, M., Cappelletti, E., & Pancani, L. (2015). The Situational Version of the Brief COPE: Dimensionality and Relationships With Goal-Related Variables. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 11(2), 295-310. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v11i2.935

Rothmann S, Coetzer EP (2003). The big five personality dimensions and job performance. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology. 29 doi:10.4102/sajip.v29i1.88

Saigh, P. A., Hackler, D., Yasik, A. E., Mcguire, L. A., Bellantuono, A., Dekis, C., Oberfield, R. A. (2016). The Junior Eysenck Personality Inventory ratings of traumatized youth with and without PTSD. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 16-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.013

Stroe, M. A. (2013). Moulding dark shapeless chaos into exuberant creation. Romanian Journal of Artistic Creativity, 1(3). Retrieved October 20, 2018

Need Help With Editing? Click Here